Tracing the Butterfield Overland Mail route through Barry County

By Sheila Harris

sheilaharrisads@gmail.com

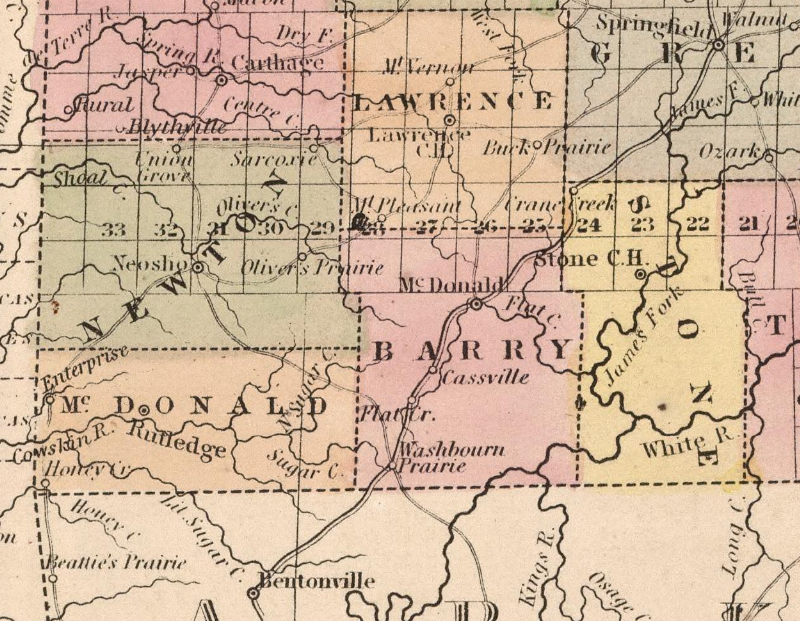

Between 1837 and 1861, depending on its usage, a trail running from the northeast to the southwest corners of Barry County was known, consecutively, as The Cherokee Trail of Tears, The Butterfield Overland Mail Route and The Wire Road.

That road, by whatever name, played a critical role in Barry County’s history, and represents our short portion of longer, national historic trails.

Much of the original trail in Barry County has been swallowed up by private land where it’s fallen victim to progress, and other sections have been paved over in a cross-patch of public farm roads. However, graveled, single-lane ribbons remain, where, with a little imagination, one can get a glimpse into the past.

About four years ago, inspired by the account of Berryville, Ark., resident and blogger, Don Matt, who, with his brother Paul Matt, scouted out the entire, original national Butterfield Stage Route in the 2004, I decided I’d do the same thing right here in Barry County. Turns out, even on a smaller scale, the search was challenging.

Once the only connecting artery between Springfield and Fayetteville, “The Indian Trail” – as it was called by early explorers – was formed by semi-nomadic Native American tribes in the Ozarks, including members of the Osage, Delaware, Kickapoo, Quapaw, and Caddo tribes, as they traveled between trading centers and hunting lands.

The trail’s name took on grim significance in 1837, when it was dubbed the “Trail of Tears” by members of the Cherokee Nation. After President Andrew Jackson signed The Indian Removal Act into law in 1830, members of the Seminole, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek) and Cherokee (so-call “Civilized Tribes,” because they had adopted many aspects of European-American culture) were driven like cattle by the U.S. military, from their ancestral homes in the southeastern United States, to promised reservations in “Indian Territory,” now the state of Oklahoma. The Cherokee were the last to make the forced march across 1,000 miles of land, where they lost as much one quarter of their 16,000 tribe members to starvation, exhaustion and exposure.

“After every overnight stop [one of which was recorded on early Barry County settler John Lock’s property near Brite Spring, south of McDowell, and another at McMurtry Spring, south of Cassville], we buried the dead in the morning,” states the account of one soldier.

“Even in the thick of battle, I’ve never seen human cruelty and suffering like what I saw on that journey,” said another.

In some cases, homesteaders along the trail provided food for the travelers, attempting in the best way they could to alleviate the suffering they saw.

The account of one Stone County writer tells of a baby girl wrapped up in a blanket and left beneath a tree by a desperate Cherokee mother. The property owners found her and raised her as their own, and she became known as “Indian Annie,” the account states.

The last detachment of Cherokee on the Trail of Tears passed through Barry County in 1839.

In 1857, John Butterfield, an enterprising gentleman from New York, signed a contract with the U.S. Postal Service for $600,000, per annum, to deliver mail twice a week from points in St. Louis and Memphis to a terminus in San Francisco. Butterfield’s proposed route won favor because of its arcing “oxbow” course through the southwest, designed to avoid wintry mountain passes. His ambitious plan got underway in 1858.

The mail, along with passengers, left from Memphis by boat, where the cargo was transferred to Butterfield coaches in Fort Smith.

From St. Louis, the mail was delivered by rail to Tipton, Mo. – the site of the first Butterfield Overland Station on the east end of the route. From Tipton, the mail route dropped south into Springfield, where it picked up the Trail of Tears and ran southwesterly toward Fayetteville, then dropped into Fort Smith.

Passengers from Tipton to Fort Smith rode in ornate Butterfield stage coaches with padded seats and enclosed cabs.

From Fort Smith, westward, however, passengers rode in “celerity wagons,” in which comfort was not prioritized. Designed to be lighter in weight to facilitate rougher terrain, the celerity wagons featured slab seats and an open wagon, with canvas or leather curtains that could be dropped.

During the 25-day journey, in both models of transport, passengers slept on the coaches, if they slept at all. The rows of three inside seats were engineered to fold flat into beds, where the passengers cozied up while the wagons lumbered onward.

The coaches were pulled, ideally, by four trained horses. History records, however, that untrained animals — including mules and wild mustangs — were often conscripted, and, when they ran amok, were the cause of a few deaths, according to an 1860 article in The New York Herald.

The same article states that no one was ever killed by an outlaw on a Butterfield stage. Valuables were not allowed onboard, so Butterfield didn’t see the need for anyone to ride shotgun beside the driver. The passengers, however, must have felt differently, since most of them were typically armed.

A Cassville resident who grew up in a cabin at Brite Spring, southwest of McDowell — across from the historic property of John Lock, one of Barry County’s earliest settlers — remembers being told about the “the hanging tree” across from her home.

“Our parents told us that tree was where they took care of stage coach robbers,” she said.

In Barry County, Butterfield coaches made stops to change horses in three locations, where passengers had the opportunity to disembark and buy refreshments from what were commonly called taverns. When entering the county from the northeast, the first stop was at the John Smith Station, located beside Wise Spring.

The original concrete Butterfield marker stands beside the spring house on this park-like, private property, where the site of Smith Station is also commemorated. While explorers are not welcomed with open arms, neither are they forbidden from venturing down the inviting trail.

Several miles southwest of Smith Station, and six miles northeast of Cassville, travelers stopped at the John D. Crouch Station, where the original Butterfield marker is located beneath a tree on the northwest side of the road. This marker is easy to overlook, and one I’ve passed by numerous times without noticing its presence. A young man, whose family has lived in the vicinity for generations, pointed out where he’d been told the old station once stood.

For Butterfield travelers, the southernmost stop in Barry County was at the John Harbin Station, located one mile southwest of Washburn. Because no marker remains, its precise location has long been a matter of debate, says blogger Don Matt, although, for him, the case was settled after chancing upon rural Washburn resident, Roberta Ellis, who was out tending her lawn.

“Mrs. Ellis knew exactly where Harbin Station once stood,” Matt said. “In fact, she told me she was a descendant of John Harbin.”

Mrs. Ellis took Matt up the narrow lane on her property and showed him where the station had been. She also gave him a copy of an old photo depicting the house that had been built on the foundation of the station, which had been burned during the Civil War.

Mrs. Ellis passed away in July 2022, taking much of Washburn’s oral history with her.

Located on private property on a rise to the east of Highway 37, about a mile south of Washburn, the site of Harbin Station is not accessible to the public. However, just a bit farther south, Farm Road 1050 (Rock Springs Road), which turns west from Highway 37, is. For Barry County history buffs, it’s a road I highly recommend traveling, although I advise taking good company and a four-wheel-drive vehicle.

In turn, a Cassville resident advised me to take care on the entire trail, as the residents along some areas, he says, have a reputation for being hostile.

On Farm Road 1050, remains of a bygone era abound, including a lengthy rock fence in a field to the southeast of the road, probably built by slave labor and later used as a bulwark by Civil War troops, the current property owner surmises. Not far from Highway 37, the road winds deep into a valley, turns to gravel and narrows to a single lane, where it runs alongside Little Sugar Creek to the Arkansas line and makes its way to the back gate of Pea Ridge National Military Park. It’s on this stretch of the trail that a person can get a true feel for what early travelers might have seen.

The Butterfield Overland Mail ceased operating in 1861, preceding the onset of the Civil War in April of that year.

During the Civil War, the trail through Barry County was used for military communications and travel and became known as the Wire Road. Sections of the route – the site of many military skirmishes and much mayhem between Wilson’s Creek (to the northeast) and Pea Ridge (to the southwest) — still bear the name “Old Wire Road,” including a stretch through Washburn on Highway 37.

When Highway 37, which ran northward from the Arkansas line through Cassville and Monett, was completed in 1922, presumably the Old Wire Road became less traveled.

In 1987, The Cherokee Trail of Tears was designated a National Historic Trail by U.S. Congress.

The original Butterfield Overland Mail route was designated a National Historic Trail by Congress in December 2022.

For the sake of preserving local history, I challenge you to look for our part of this all but obsolete, and nearly forgotten, trail. Better yet, take your kids and grandkids with you, and tell them what once happened on that road: right here in Barry County.

To locate the approximate route, visit the Barry County Museum and read Don Matt’s blog at https://butterfielddaytwo.blogspot.com/.