SHELL KNOB TAB: Carved in wood, by Stone

Native American sculptor offers creations at Turtle Crossing Gallery

By Sheila Harris sheilaharrisads@gmail.com

Turtle Crossing Gallery is a marvel worth exploring — as much a museum, as it is an art gallery, visitors say.

Located in a shady alcove just a short, scenic drive on YY Highway past the Central Crossing Senior Center in Shell Knob, the attraction of the gallery can be credited, in part, to the artists themselves: Stone and Karol Akin, who met 17 years ago in Eureka Springs while attending a ballroom dance.

Native American culture and history are Stone’s passions, and, for those interested, he’s willing to share what he has learned over the years.

Stone said he was sent to live with his grandparents as a young boy, a transition he credits with setting him on his path to becoming a wood sculptor. Native Americans of the Blackfoot and Cherokee tribes, Stone’s grandparents lived in a remote area in the Bootheel of Missouri, outside of Fredericktown.

“They were naturalists,” he said. “We didn’t have water or electricity, and we raised everything we ate.

“I was young and sickly when I moved in with them – seven years old or so – and my grandma would send me outside with a butcher knife and a piece of kindling, and tell me to carve my foot,” Stone said.

So, using his foot as a model – a foot that was almost always bare — Stone said he attempted to carve a wooden likeness of it, over and over.

“If Grandma wasn’t satisfied with my attempt, she threw it into the fire and told me to start again,” he said.

Stone said he attended a rural, one-room schoolhouse where 12 grades were taught.

“When I was 14, I started doing construction work to earn money,” he said.

Those skills ultimately paid his way through college, where he earned a degree in Architecture before pursuing a Doctorate in Theology. From there, the world was his oyster, one which he traveled extensively in search of knowledge about the culture, anthropology, ethnology and the differences in spirituality between Native American tribes. His journeys took him to 183 different tribes in locations including Guatemala, Honduras and the Southwestern and Eastern United States.

Native American history and “the greatest ethnic cleansing that’s ever been” are topics that Stone is passionate about. That passion came to the attention of movie producers, and Stone will soon be the interviewee for a documentary being made about Cherokee history.

Today, Stone said, there are about 550 federally-recognized tribes in the U.S., 500 state-recognized tribes and many more tribes not recognized at all.

Stone believes one of the largest tragedies perpetuated against Native American tribes was the kidnapping of their children by U.S. government agents in the mid to late 1800s and continuing into the mid 1900s. Under the guise of “Americanizing” the children, they were transported long distances and incarcerated in what became known as “Indian boarding schools,” for the purpose of ridding them of their Native American culture.

“Their hair was cut and they were made to wear Euro-American clothing and speak only English,” Stone said.

According to a report by the U.S. Department of the Interior, released in 2022, the U.S. government operated or supported 408 boarding schools for Native American children between 1819 and 1969.

“My great-grandmother ran away from one of those schools as soon as she found the opportunity,” Stone said.

Now, Stone laments the increasing loss of many Native American languages.

Stone’s professional career as an architect was spent primarily in Colorado and Michigan, while the wood-carving skills that he acquired as a child — although honed consistently throughout the ensuing years — were nothing more than a hobby.

In 2004, that changed, when Stone was debilitated by a 28-foot fall that broke 11 bones in his body.

“There wasn’t much I could do [physically] after that,” he said. “So I turned to my artwork and made it a profession instead of a hobby.”

Artistic ability comes naturally to Stone, who said he’s never had any professional art training. Using nature’s materials and the natural world as his model, Stone’s creations are, for the most part, faithful reflections of the work of their original creator.

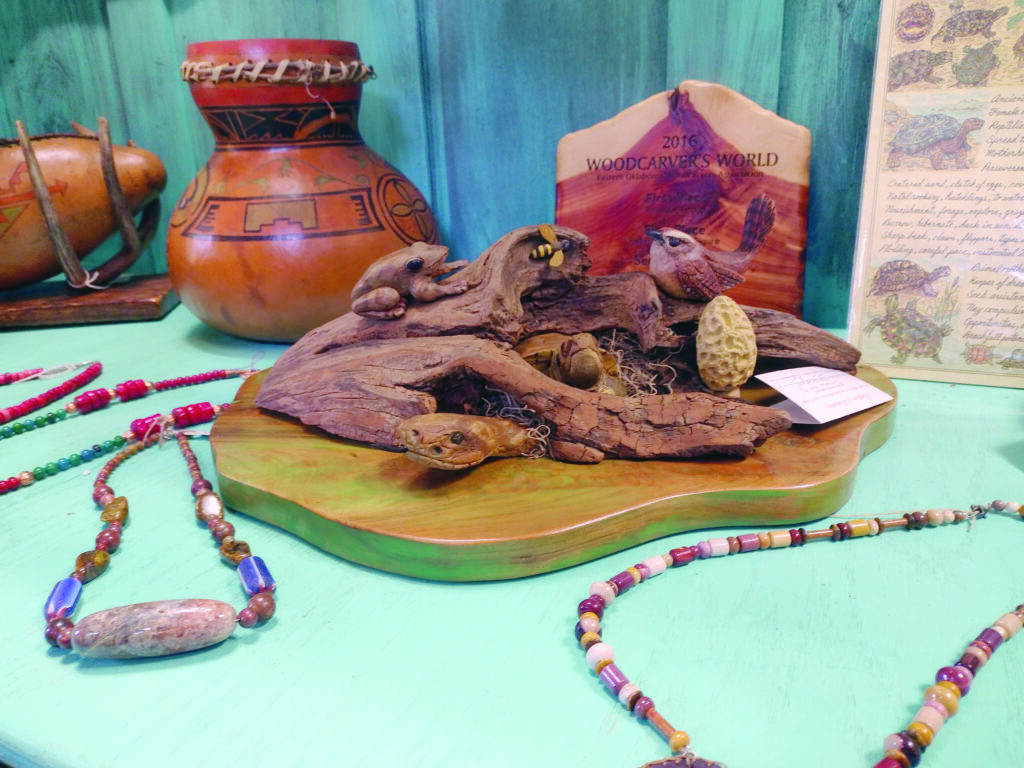

Stone said wood sculpture is his favorite art form, although he also paints, using various mediums and backgrounds, and makes jewelry – and many of his pieces are a combination of all three.

Intricately carved box turtles are his specialty, and the creatures for whom the gallery is named.

“No two are alike,” he said, a statement that can be made of every creation in Turtle Crossing Gallery.

“When I first met Stone, and he showed me his artwork, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” Karol said. “Everything he made was so detailed, so beautiful, and he wasn’t doing anything with it.”

Karol changed that.

She began entering several of his pieces in art shows around the country, and, soon, awards were coming in, including several first and second places in national competitions.

In spite of his awards, Stone said it’s easy to stay humble in the art world.

“You can always look around you at these art shows and find someone who’s more talented than you,” he said.

Stone is not the only artist at Turtle Crossings Gallery. Karol, a retired RN and licensed massage therapist, is a creative seamstress and makes unique dolls and bags, as well as unique centerpieces and shelf arrangements using natural materials – often with one of Stone’s wood creations tucked in.

Everything in Turtle Crossing is for sale, say the Akins, including the entire gallery, if a person is interested in buying it.

The gallery building itself is a work of art, flooded with natural light and created board-by-board with Stone’s two hands.

A visit to see the building itself is well worth the few minutes’ drive to get there, but the fairyland of artwork that greets a person when they enter the door is a breath-taking complement to the building’s exterior.

And, if you’re lucky, you’ll get a lesson in Native American culture and history from the gallery’s artists in residence.

Turtle Crossing Gallery is located at 26809 Apache Lane in Shell Knob. Hours are Thursday to Sunday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., or by appointment by calling 417-669-8035.