THROUGH THE YEARS MAG: Sweet sorghum — A family tradition continues

By Sheila Harris

Sherry Leverich Lotufo, of rural Exeter, said her family’s sorghum-making tradition began in the 1970s, quite by accident.

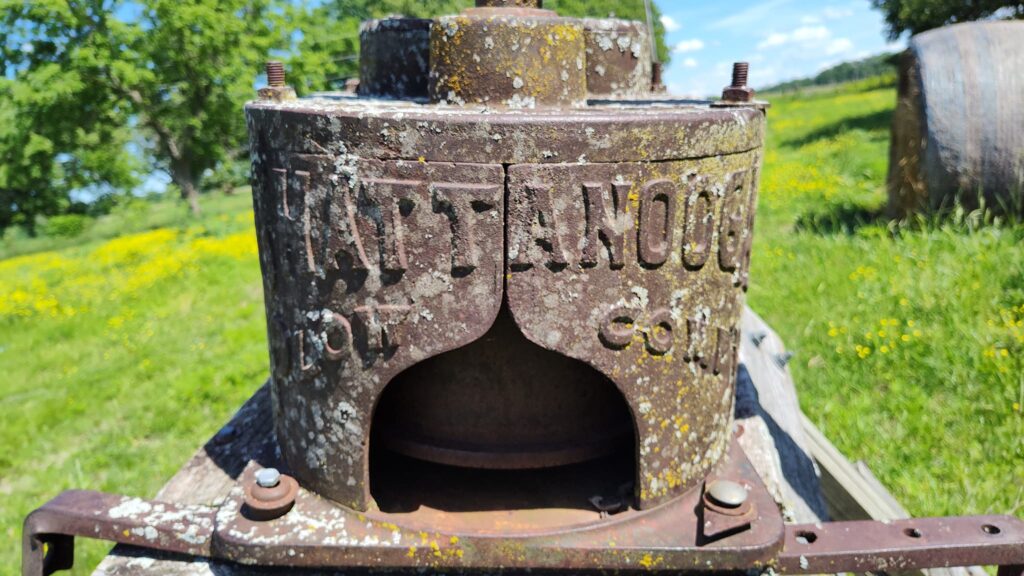

“My Uncle Milt (Johnson) ran a road grader for the Corsicana Road District, where my Uncle Milt and Aunt Helen had a farm,” Lotufo said. “One day, while he was grading, Uncle Milt found pieces of an old Chattanooga sorghum mill lying in the ditch, made out of solid cast iron and dating back to the 1890s. Uncle Milt called my dad [Don Leverich] to help him, and the two of them loaded the pieces of the mill into my uncle’s pickup, then they put the mill back together at his house.”

Decades of yearly sorghum-making followed.

“I’m not sure where my dad and uncle learned how to make sorghum, but they seemed to know what they were doing,” said Lotufo, who was too young to remember the details when the mill was first put into service.

However, she learned how to make sorghum herself in the years that followed.

“We had big, family sorghum-making gatherings every fall,” Lotufo said. “My dad would let me and my brothers help decide when it was time to harvest. He’d walk down the rows of cane with us and cut off six-inch pieces for us to chew on. If the juice in the center was sweet enough, we’d start the harvest.”

Used as a natural sweetener, sorghum is obtained by pressing the sweet center juice from sorghum cane, then boiling it to condense it and to remove impurities. The principle is similar to the processing of sugar cane.

“A lot of people refer to sorghum as ‘molasses,’” Lotufo said. “But, they’re two different syrups. Molasses is from sugar cane; it’s the byproduct after sugar cane is processed.”

Sorghum, when processed, is deliciously sweet, with a distinct flavor much milder than that of molasses. Lotufo’s sorghum is the whole product, with nothing added, she said.

“I use sorghum for cookies and candy and in other ways you would use syrup,” she said.

Don Leverich passed away in 2002, and Milt Johnson several years before that, but Lotufo and her mother, Alice Leverich, kept up the sorghum-making tradition until 2014, when Alice’s health began to decline.

After her mother’s passing last year, the onus for handing down the sorghum-milling know-how was on Sherry Lotufo’s shoulders, if it was to be passed on.

“I had several younger cousins who’d been asking me to teach them how to mill sorghum,” Lotufo said. “How could I say no?”

Lotufo said, in late June, she planted about one-quarter of an acre of sorghum cane – 10 rows, each 100-feet long — on her farm outside of Exeter.

“It only takes the crop about 100 days to mature,” she said.

While rain is beneficial, Lotufo said the drought this summer condensed the juice in the center of the canes, which made it extra sweet.

“Sweet sorghum,” Lotufo said, is a very specific type of plant. Although there are a variety of types, the seeds are only sold by a few outlets. Lotufo orders hers from a producer in Kentucky.

“My dad really liked the sorghum he grew from seeds he got in the 1980s from a producer at Silver Dollar City,” she said.

By mid-October, Lotufo’s sorghum was ready for harvest. She had lots of help with the enterprise from her husband, Rob, and her sons, cousins, friends and neighbors.

At harvest, sorghum stalks are cut down by hand, as close to the ground as possible, then the leaves and seed-heads are trimmed off.

“We don’t use the seed-heads for anything except feeding birds in the winter, unless we’re saving seed for next year,” Lotufo said.

The stalks are placed in bundles, with stalks all lying in the same direction, and are transported to the sorghum mill in trailers or pickups.

Lotufo said, after 10 years of not being used, the old mill itself needed an overhaul this year, a job that fell to her husband.

The mill operates by horse, mule, four-wheeler or riding-lawnmower power, Lotufo said. A log attached horizontally atop the mill shaft is turned by an animal or motorized vehicle that makes laps around the mill until the job is complete. Either way, human guidance is needed.

The milling process is tedious. Stalks must be fed into the mill, four or five at a time. The juice expressed from the centers of the cane is channeled into 10-gallon milk cans, and, from there, placed in large rectangular pans over an open fire pit for cooking.

“It took about four hours to run the sorghum through the mill this year,” Lotufo said. “Then, it took another two-and-a-half hours to cook it down.”

Lotufo said her cooking method is “kind of archaic.”

“Dad used a piece of sheet metal to create a large, rectangular pan that sits on top of a rectangular fire pit,” she said.

Lotufo calls it the “batch pan method.”

As the sorghum cooks and condenses, the impurities rise to the surface and are skimmed off.

“For every 10-gallon batch of syrup we cook, we get about one gallon of sorghum,” she said.

Lotufo divides the sorghum into pint jars for distribution among those who play a part in its production.

She said the sorghum planted this year yielded about 40 gallons of raw juice, which cooked down to four gallons of finished sorghum.

“I want to plant twice as much sorghum next year,” she said.

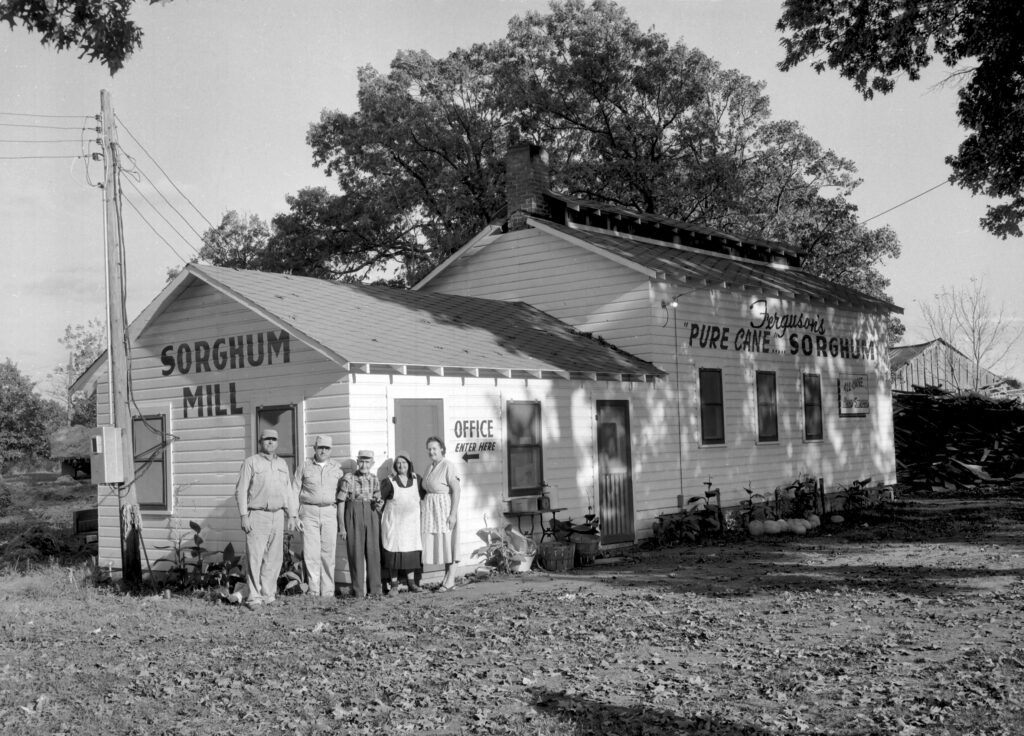

In Barry County, sorghum was once processed on a large scale by the Hankins/Ferguson Sorghum Mill and the Henbest Sorghum Mill, both located near Butterfield. Area farmers grew sorghum crops, then brought them to the mills for processing, where they paid millers either in cash or with two-fifths of their sorghum yield. More information may be found at: https://www.barrycomuseum.org/pages/Sorghum.html

As processed sugar became cheaper and more readily available, farmers quit growing sorghum, and the need for large sorghum mills disappeared. The milling craft lives on, however, with a few farmers like Lotufo.

While milling sorghum could perhaps be learned by trial and error, by reading an article or watching an instructional video, it’s best learned hands-on, at the knees of previous generations, Lotufo believes.

She’s pleased to play a part in handing down that tradition.