Smiles and civilization

Monett Museum exhibit honors Harvey Girls

By Jessica Breger Special to Monett Monthly

Monett is known for being a railroad town, with men such as B.F. Hobart and Henry Monett credited for the success of the town and its involvement with the The St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco).

In honor of March as our National Women’s History Month, the Monett Historical Society and Museum is looking at some of the women who made the early days of the Frisco line hospitable, for railroad workers who built the town and travelers alike.

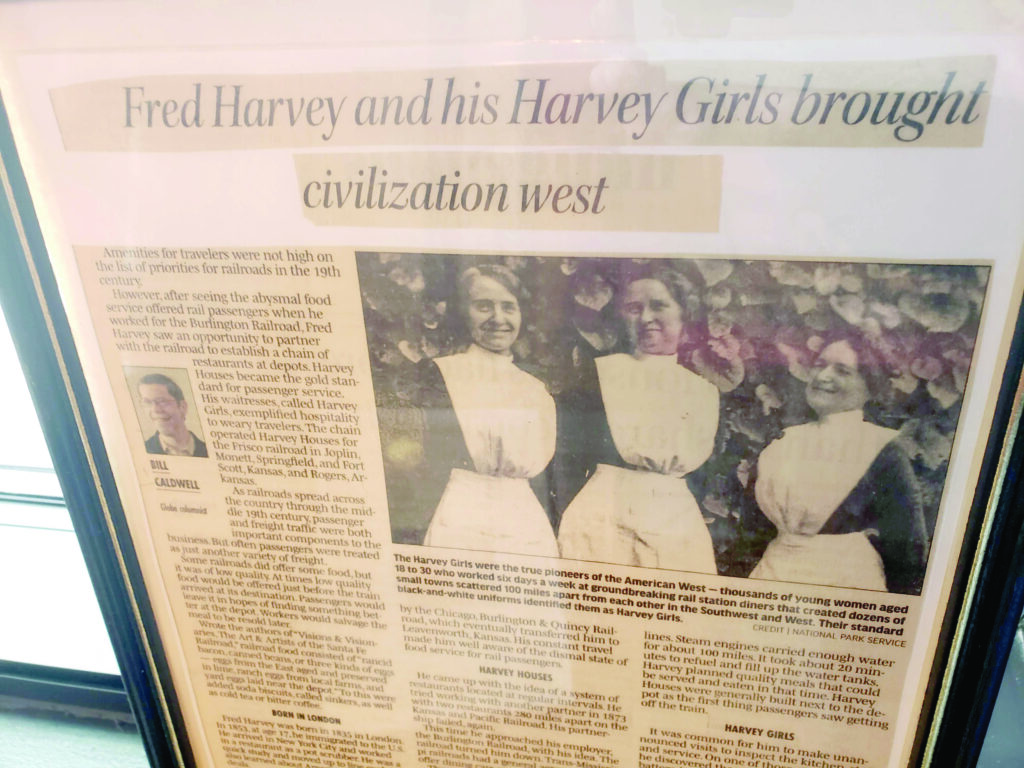

The Harvey Girls became a name synonymous with the Frisco Railroad and high quality hospitality, something previously not expected by hotels or restaurants serving railroad workers.

Frederick Henry Harvey opened up the first Harvey House in 1878 in Florence, Kan., to provide quality dining and lodging for those working and traveling on trains across the country.

Having worked on the railroads himself and was unhappy with the food service in the railroad industry.

Initially, Harvey had employed male waiters to work his restaurants and hotels. He found that the establishments were wrought with the familiar issue of fights among not only guests, but servers as well.

After the wives of several employees had stepped in to work in place of their husbands, Harvey knew who could save his vision of upscale service, so he turned to the young women of America for help.

Harvey began to advertise in newspapers across the country to hire “Harvey Girls.” The newspaper advertisements looked for women between the ages of 18 and 30, “of good moral character, adventurous and intelligent” to fill the roles of waitresses in his restaurants.

Applicants were expected to be single, well mannered and have an eighth-grade education. These women would become what was known as one of the first all female workforces in the country.

This employment opportunity was unique in the late nineteenth century, as women had few opportunities to work or to leave the family before they were married.

Young women traveled from across the country to work at the Harvey Hotels, which provided a new hope of independence through employment, housing and training not previously available.

Harvey Houses offered these women contracts for six months, nine months, and one year of employment.

The women were employed at $17 a month, with a dorm and work attire provided. As stipulations of their employment, the women were not allowed to marry within the first year of employment and were closely supervised in their provided housing.

Harvey’s rule restricting marriage came about as he noticed several newly hired waitresses would tend to marry customers and end employment before they had worked a full six months.

Harvey Girls were not permitted to flirt with customers and wore a modest uniform to dissuade any notion that the women provided anything other than superior waiting services.

Harvey Girls were to live in housing adjacent to the restaurant, where they adhered to a curfew and only chaperoned male visits. The women were also given etiquette classes which focused on providing customers with a pleasant smile in all circumstances.

The Harvey Girls are often described as one of the first workforces made up of all women in the Southwest and were said to set the gold standard in the hospitality industry along the American railroads.

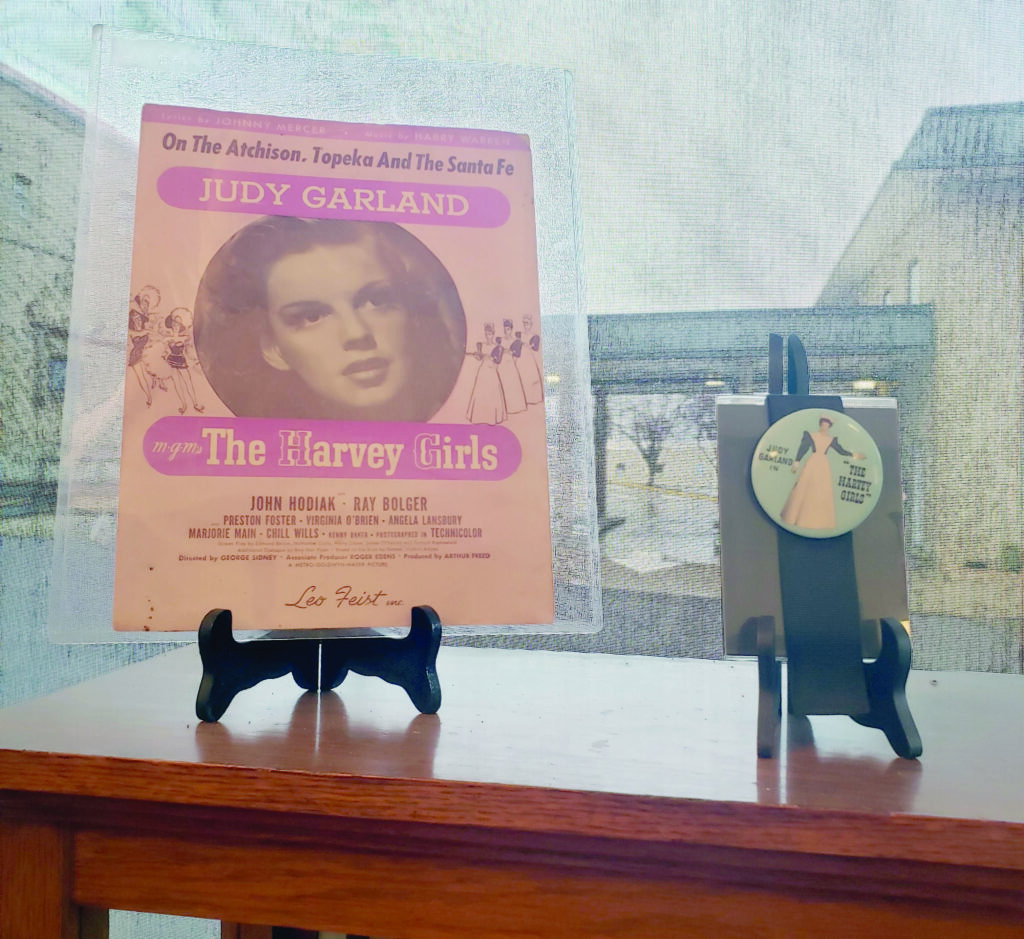

The high standards, professionalism and loyalty of these women became so well known that the Harvey Girls were even immortalized in film.

The image of the Harvey Houses’ staff was brought to the silver screen in the 1946 movie “The Harvey Girls” starring Judy Garland.

In the film, Garland plays a young woman who begins work at a Harvey House restaurant and leads the staff of women to defend their restaurant from competitors.

The film displayed the courage, dedication and skill labor that it took from young women at the time to gain independence and bring civilization to the wild west.

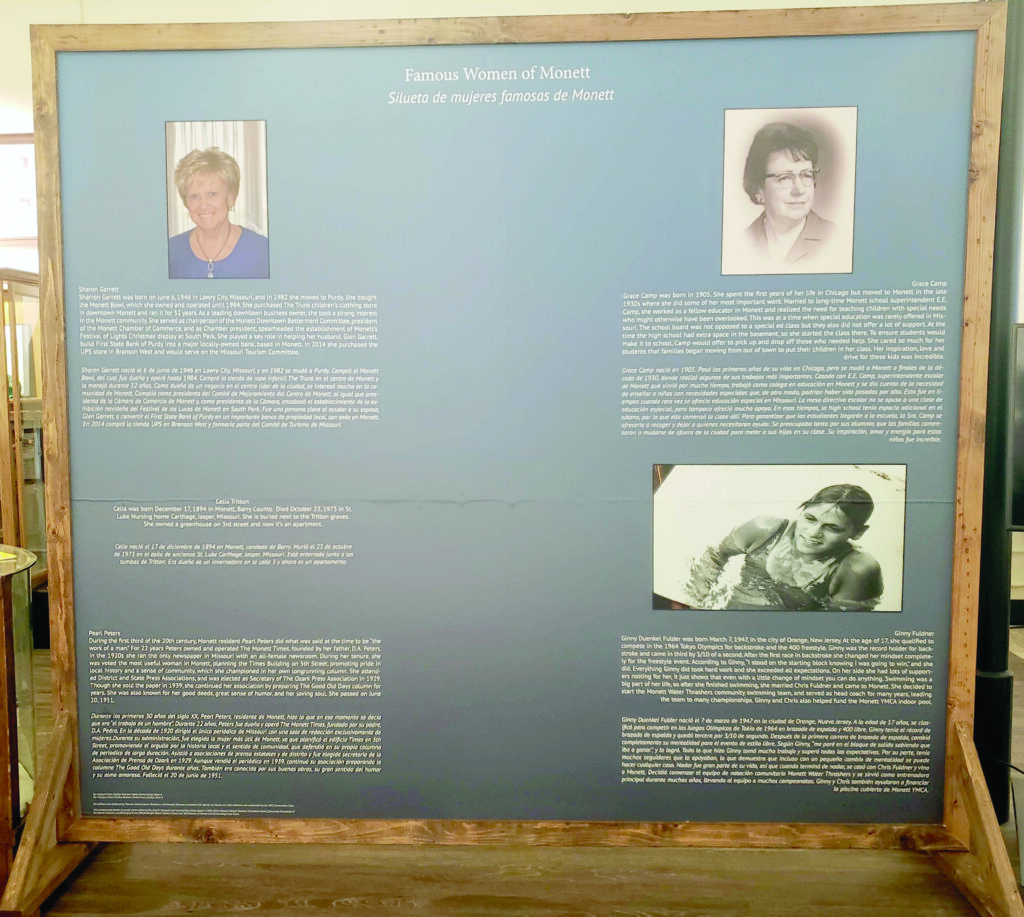

Along with displays honoring the Harvey Girls and their contribution to the area, the Monett Historical Society and Museum honors several women who have made their mark on the town to visit during Women’s History Month.

Learn about Monett’s historical women, such as Grace Camp, who introduced the special education program to Monett schools, and Pearl Peters, who operated The Monett Times in the 1920s as the only newspaper in Missouri with an all-female news staff.

The Museum is open five days a week, Tuesday through Saturday from 10 am. to 4 p.m. Admission is free.