By Sheila Harris sheilaharrisads@gmail.com

Claiming a mere 15 miles or so in length, Roaring River is one of the shortest rivers in the nation, but its source, Roaring River Spring, has captured the imagination of mystery-lovers since time immemorial.

Churning out an average 20.4 million gallons of water a day, the spring is the 20th most prolific in Missouri. Other measurements and details connected with Roaring River Spring, however, have been elusive.

Breadth

Dye-tracing tests to determine the breadth of the spring’s recharge basin (the perimeter area from which it draws water) have been completed, announced hydrologist Ben Miller, in an email to the Cassville Democrat on January 29. Miller, a volunteer with the Cave Research Foundation, has been working in conjunction with fellow volunteer, Bob Lerch, and Roaring River State Park personnel for the last several years to determine the extent of Roaring River Spring’s recharge basin.

“[We now know] the total size of the Roaring River recharge area is 47.34 square miles,” Miller said. “Its northwestern-most corner is in Shoal Creek, upstream of the Highway 76/86 junction [just south of Wheaton].”

Wheaton is located over 20 miles away from Roaring River Spring.

Miller says he and other volunteers are in the process of writing up the results of their work for an upcoming issue of Missouri Speleology.

“This effort was the first major attempt to determine what areas contribute flow to Roaring River Spring,” Miller said. “Understanding the area which drains to Roaring River Spring can help efforts to protect the spring and preserve the area for future generations.”

“Becoming aware of the sheer scope of Roaring River Spring’s recharge area will give people an idea of how easily our water supply is affected by contaminants located miles away from it,” Lerch said.

“For example, if a chemical tanker overturned on Highway 37 in the Washburn area, any spilled chemicals would almost surely make their way into Roaring River Spring,” Lerch explained in a 2021 interview.

In addition to the scope of Roaring River Spring’s recharge basin, the dye-tracing tests revealed quirky mysteries of nature.

For example, dye injected into upper Shoal Creek, beyond the Highway 76/86 junction, showed up in Roaring River, but dye injected into a local phenomenon, the Exeter Sinkhole (more on the sinkhole later), which lies closer to Roaring River Spring, flowed in the opposite direction, north toward Thomas Hollow.

An equally fascinating conundrum occurs in Butler Hollow, south of Seligman. There, Lerch said, Roaring River Spring shares a portion of its recharge basin with Blue Spring – near Eureka Springs, Ark. – to the south.

“Some of the water [in Butler Hollow] goes [southwest] to Blue Spring; some goes [north] to Roaring River,” Lerch said. “The water that goes southwest actually has to run beneath the White River in order to reach Blue Spring.”

Such are the mysteries of southwest Missouri’s underground karst environment.

Karst: Caves, Sinkholes, Springs, Losing Streams

A Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) publication called “Conserving Missouri’s Caves and Karst,” details the natural characteristics of what lies below the Ozarks Plateau, in the surreal world of karst underlayment.

Characterized by soluble, constantly eroding dolomite and limestone bedrock, karst is pocked with fissures, conduits, losing streams, rivers, sinkholes, cave systems and springs. All kinds of holes, in other words. Geologists often compare karst geology to Swiss cheese.

According to the Missouri Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Missouri has 4,400 springs and 7,500 recorded caves – hence its nickname, “The Cave State.”

The majority of both features are located in the Ozark Plateau, commonly called “the Ozarks.”

Barry County, alone, contains between 201 and 400 caves.

In addition to Roaring River Spring’s submerged cave, the history of Cassville records two large, once commercially-operated, cave systems.

A portion of Crystal Caverns, a cave system which lies beneath the northern outskirts of Cassville, was once open for public tours as a commercial enterprise. Shuttered in 1994, the extent of its sprawling underground footprint remains an unknown.

According to history, Barry County officials stored county records in another cave system — Rockhouse Cave — for safekeeping during the Civil War. However, the historical use of Rockhouse Cave, which lies about seven miles east of Cassville, long predates the Civil War. Archeological records and artifactual evidence indicate that the cave was once used for the manufacture of tools by early Native American tribes. Older residents of Barry County recall that Rockhouse Cave was once open to the public and was a popular hangout for teenagers.

Caves are not the only natural phenomenon in Barry County’s karst topography.

In February 2005, a giant hole opened in the earth and filled with water, then incrementally swallowed hundreds of square yards of pasture in a valley southwest of Exeter. Known locally as “The Exeter Sinkhole,” the unsettling event was the talk of newsprint and airwaves for months to follow, until the breadth of the gaping hole ceased expanding. Before stabilizing, the crumbling earth undermined an adjacent farm road, which is now closed to through traffic.

While the Exeter Sinkhole is more dramatic than most, it’s a common feature of karst underlayment. Hundreds of such pits (most of them smaller) dot the Ozarks’ landscape, in cities as well as in rural areas.

Sinkholes and their karst cousins, losing streams, are portals through the earth’s surface that provide direct routes to groundwater below.

The interconnected web of karst features (Swiss cheese, if you will) below the Ozarks allows virtually unfiltered groundwater to move freely and rapidly, “an average of one mile per day,” says Tom Aley, author of an article in the MDC publication. By comparison, he states, groundwater travel-rates within non-karst areas are commonly only a few feet per year.

The DNR’s website said water entering a sinkhole in the Ozarks can travel through subterranean groundwater conduits for 30 miles or more before surfacing in springs and wells.

Where water in the Ozarks comes from and where it goes can be anybody’s guess.

That’s the beauty – and the mystery – of karst.

Depth

The depth of Roaring River Spring is a statistic that remains tantalizingly out of reach, although, over the past years and decades — a century, even — multiple attempts have been made to nail down that elusive number.

Goodspeed’s 1888 History of Barry County describes Roaring River Spring as “fathomless.” In following years, the sons of early settlers — brothers with the last name of Ball — rowed a boat to a position above the spring, then dropped a weighted line into its maw. The results of their attempt were inconclusive, with history recording depths varying from “bottomless,” to 125 feet, to 300 feet.

In more recent years and using more precise technology, various teams of divers have taken turns attempting to plumb the depths.

Divers Roger Miller and Frank Fogarty, of Louisville, Kent., explored to a depth of 215 feet in 1979, followed by divers Roger Gliedt and Dave Porter some 10-15 years later. Both pairs of divers agreed that there was a hang-up at depth: a restriction at 225 feet that prevented deeper penetration.

In August 2021, however, members of the KISS (Keep It Super Simple) Rebreathers dive team, led by Mike Young — who owns KISS Rebreathers USA, based in Barling, Ark. — penetrated that restriction using rebreathers. The newer technology of rebreathers (underwater breathing equipment that reuses the oxygen in divers’ exhalations) provides a slimmer subsurface profile than the bulky air tanks used by traditional SCUBA divers and thus made passage through the restriction possible.

On Nov. 12, 2021, Young and KISS Team Member Randall Purdy, dove beyond the restriction to a depth of 472 feet below the water’s surface, to establish Roaring River Spring Cave as the deepest in the nation. That record was later broken when a diver in Phantom Springs Cave in West Texas reached a depth of 570 feet. Roaring River Spring, however, remains the deepest explored spring in Missouri.

“There still more depth down there to explore,” Young said after the record-establishing dive.

Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) operator, Steve Haggitt, of Prince of Wales Island, Alaska, has intentions of breaking the KISS team’s record. Haggitt, a commercial diver by trade, has been using remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) to inspect underwater infrastructure and subsurface ecological conditions at pollutant discharge sites for government entities for the past four years. He says much of his work is in multi-level, confined spaces, similar to caves.

Haggitt brought three ROVs and additional manpower to Roaring River Spring in April and May 2024 to plumb the depths. However, due to inclement weather, which resulted in excessive discharge rates of water from the spring, and the sub-surface entanglement of the tethers on his ROVs, his machines were unable to penetrate beyond the 225-foot restriction.

In spite of the obstacles, Haggitt’s hopes remain high for a return trip to the spring and another stab at reaching “the bottom,” at a later date.

The KISS Rebreathers dive team’s exploratory mission was abruptly curtailed in 2022 after the death of 27-year-old diver Eric Lee Hahn. The team’s 2024 application for further exploration in Roaring River Spring was denied.

Tamara Thomsen, maritime archaeologist for the State Historic Preservation Office in Wisconsin, does not believe that human divers and ROVs are mutually exclusive.

“There’s a place for both ROVs and human divers in underwater exploration,” Thomsen said.

A technical diver herself, Thomsen routinely puts both divers and ROVs to work when researching historic shipwrecks that are found in the bottom of the Great Lakes.

“There are good reasons to use ROVs when researching,” said Thomsen, who sometimes spends four hours a day in the water. “The protection of human life is an obvious consideration. ROVs can go deeper and remain at depth for extended periods of time in situations that would be next to impossible for humans.”

Data collection is another attribute ROVs have going for them, Thomsen said.

“They can collect hours of data, including multiple 4K photos, at speeds and in depths that humans could never accomplish,” she said.

However, Thomsen says, ROVs are limited to the frame of what their cameras can see.

“In that sense, they’re no replacement for a diver,” she said.

She added that ROVs can cause damage to historical artifacts, simply because they’re a machine, citing the example of the mast of a historic underwater shipwreck being toppled by the tether of an ROV.

“I’ve worked on a lot of projects where divers and ROVs work hand in hand,” Thomsen said. “A diver can take an ROV down to a safe diving level, then turn it loose to continue the descent.”

Young would like to see some type of diver/ROV collaboration for further exploration of Roaring River Spring in the future.

Critters from the cave

In addition to the unknowns of its breadth and depth, Roaring River Spring may also be home to a unique species, which could indicate that the spring is an isolated marine environment.

Based on genetic testing, there’s a “high probability” that Roaring River Spring Cave is home to a unique species of amphipod, says Dr. Fernando Calderon Gutierrez, a marine research scientist with Texas A&M in San Antonio and a member of the KISS Rebreathers dive team.

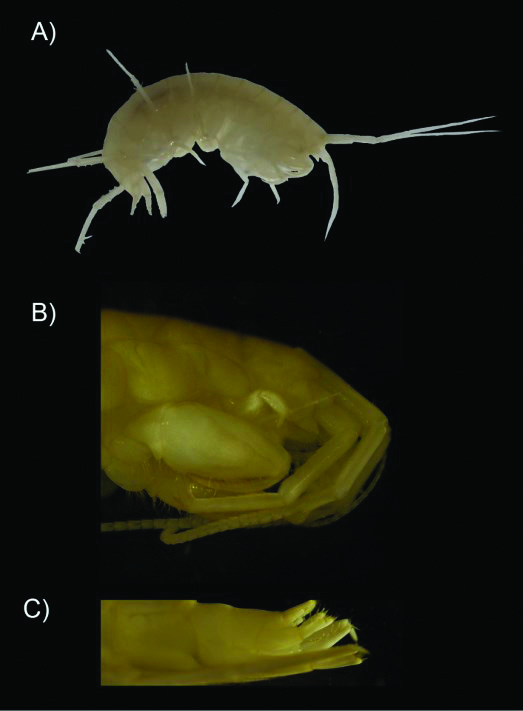

Gutierrez collected the amphipod and two species of isopods during the KISS team’s exploratory dive into the cave in September 2022. Since then, he has been analyzing and reconstructing the amphipod’s DNA sequence and comparing it to the DNA sequences of over 9,900 other species of amphipods which have been identified and named, and for which DNA information is available.

Amphipods, crustaceans which look like tiny shrimp, are common in all marine environments, including freshwater and salt water.

“So far, the DNA from the Roaring River specimen does not match the DNA of any of the other known species,” Gutierrez said.

According to Gutierrez, scientists sometimes only have fragments of the DNA information for other species, which makes comparison difficult.

“At this point, I’ve been able to reconstruct the mitochondrial genome of the Roaring River amphipod — a sequence of 16,296 letters of DNA,” Gutierrez said. “[So far], we can confirm that the amphipod is from the genus Stygobromus, and that the DNA from the sample in Roaring River does not correspond to other species with DNA sequences available.”

Gutierrez said even though it appears that Roaring River’s amphipod is a unique species, he has more comparison work to do, meaning the results of his study are still preliminary.

If the amphipod is indeed unique, it will be subject to naming using binomial nomenclature.

During the KISS Rebreathers dive team’s explorations in 2022, team biologists observed three species of crustaceans: two types of isopods and an amphipod. They also spotted a cave salamander.

Mill pond discovery

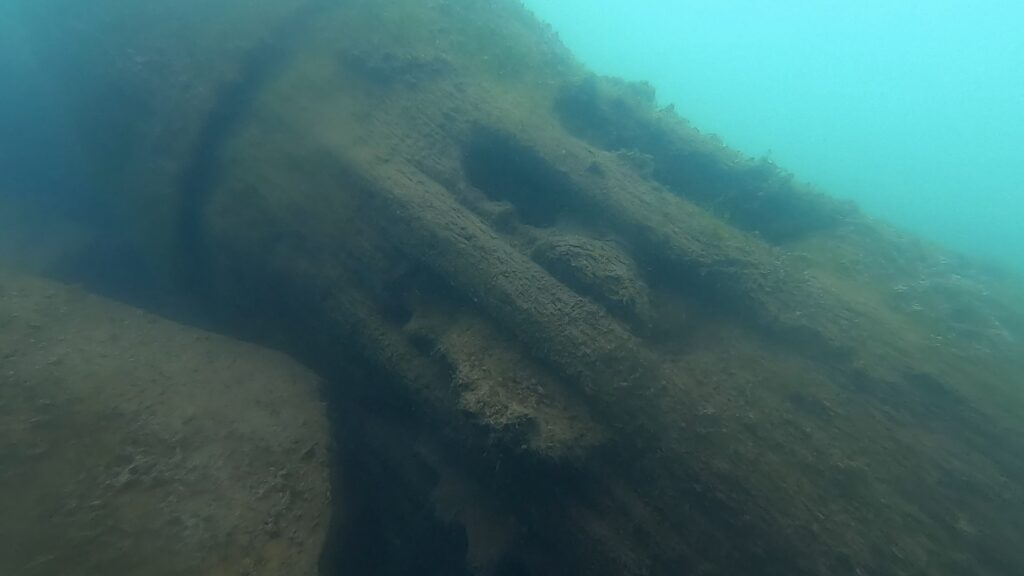

A mystery was solved (again), last October, when diver Kris Miller, with Ozarks Scuba Diving, based in Clinton, discovered the location of the remains of an old mill wheel hub known to be present somewhere below the water’s surface in the “mill pond,” or “spring lake.”

Miller, who is contracting with Missouri State Parks to remove debris from the spring lake and river, says the water wheel hub — a massive log notched with holes for paddles — is located along the south edge of the lake, not too far west of the spring.

Based on historical records, Roaring River Spring provided power for three different mills over the century after European settlers arrived in the 1830s, although Goodspeed’s says the spring could have provided the power for a dozen mills.

Early residents recorded the existence of a “primitive tub mill” in 1836, followed by the construction of a grist mill in 1845. The grist mill was destroyed during the Civil War. After war’s end, residents constructed a third mill, as well as the first version of the retaining wall around the spring to form a mill pond.

Kris Miller, who makes a living rescuing, recovering and salvaging lost underwater items, says the discovery of the old water wheel hub was an interesting historical find.

The mystique continues

Roaring River State Park consistently draws over one million visitors per year. While most of them might say they come for the trout fishing, others might attest that the sheer beauty and mystique of the hidden valley with its prolific spring brings them back year after year.