BY SHEILA HARRIS sheilaharrisads@gmail.com

Local legend and former Purdy resident, Retired U.S. Navy Cpt. Edward Estes, “flew west” on Oct. 7, 2024.

A Douglas A-4 Skyhawk, mounted in the Purdy Park, pays tribute to Estes’ service in Vietnam, service which resulted in him being held as a prisoner of war (POW) by the North Vietnamese for five years.

“Edward always knew what he wanted to do with his life,” his sister LouAnna Dodson, of Purdy, said. “He wanted to be a pilot; he wanted to fly.”

Dodson, who was five years younger than her brother, said when Edward was growing up, his bedroom was full of model airplanes, a fact not lost on visitors to their home.

“He had them everywhere – on shelves, even hanging from the ceiling,” she said.

After graduating from Purdy High School, followed by graduation from then-Southwest Missouri State College in 1955, Edward entered the Aviation Cadet Program of the U. S. Navy, and was designated a Naval Aviator in 1957. His career trajectory progressed upward from there.

While serving as an instructor pilot with Naval Air Training Command at NAS Whiting Field in Florida, he met his future wife, Bette, who was visiting Florida with friends, from her home in Lancaster, Penn.

When President Lyndon B. Johnson made the decision to commit more U.S. combat troops to Vietnam in 1965, Estes began serving his first six-month tour of duty in that country in 1966, when he made the news for making the 63,000th landing on the U.S.S. Aircraft Carrier Kitty Hawk, in the Gulf of Tonkin.

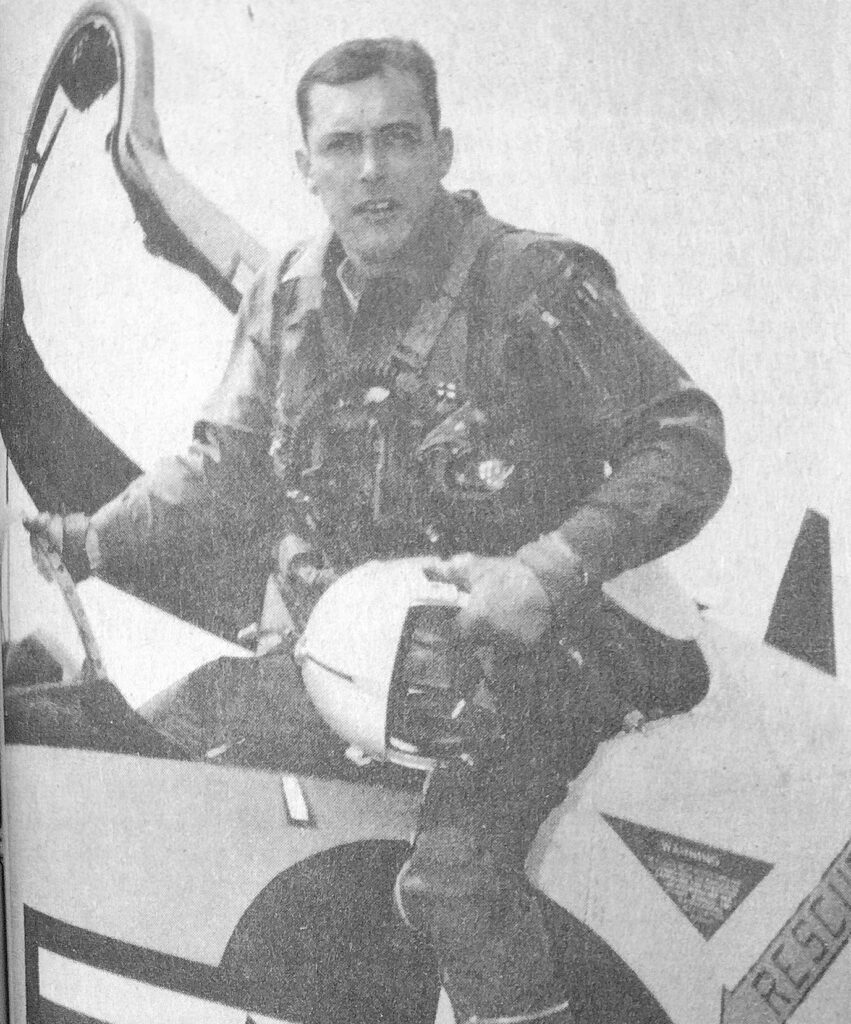

Estes afterward opted for a second tour in Vietnam. As part of a flight squadron based on the U.S.S. Kitty Hawk, Estes flew missions into North Vietnam in the cockpit of A-4 Skyhawks.

Dodson remembers well the January day in 1968 when her parents, Harold and Catherine Estes, both employees of the Purdy School District, received the news that Edward was Missing in Action (MIA) in Vietnam after his plane had been shot down.

“He had just returned to the carrier after a night mission, and was heading to his bunk for some sleep, when he was told they needed a pilot for another flight,” recalled his wife Bette, who now lives in Virginia Beach,Va. “They asked him if he wanted to take it. He said he would.”

The decision proved fateful.

On his solo mission in the A-4 Skyhawk, Edward managed to avoid two North Vietnamese surface- to-air missiles but was struck by a third one, which separated the plane’s cockpit from the fuselage, leaving him just enough time to eject.

Looking downward at the ring of Vietnamese soldiers with rifles aimed up at him, Edward later recollected to his wife, “It’s not gonna be a good day.”

Indeed, it wasn’t. Edward was taken prisoner by the waiting North Vietnamese, who loaded him into a wagon and transported him to Hanoi, where he was locked up with other U.S. Air Force and Navy captives in a facility, one of several prisons, that became euphemistically known by U.S. servicemen as “The Hanoi Hilton.”

Prisoners at the Hilton, according to Brittanica.com, were chained to floors where rats freely roamed, forced to exist in their own filth and excrement, and routinely subjected to torture.

A shower consisted of an occasional bucket of cold water dumped over them, Edward later told his wife. Meals consisted of rice mixed with pieces of gravel that resulted in broken teeth.

“I was still living at home when Edward was reported Missing in Action,” Dodson said. “It was an awful time; so quiet in our house. We’d gather at the table for meals, but nobody had anything to say. My dad would sometimes double up in grief, and repeat, ‘Oh, shoot! Oh, shoot,’ as if he couldn’t believe Edward might be dead.”

In California, Bette lived at Naval Air Station Lemoore with the couple’s two young sons, James “Ed” and David. It was a place where, although circumstances were trying, she had company.

“There were 42 of us wives at Lemoore whose husbands were MIA,” she said. “So, we were all in the same boat.”

For the next two-and-a-half years, the Estes families lived in uncertainty.

Then, Bette said, she received a six-line letter from Edward, letting her know he was alive.

Edward’s name was included on a list of Prisoners of War (POWs) released by the North Vietnamese, to the US government.

The news caused rejoicing in the Estes families. He was alive!

Knowing that Edward was in prison and alive was better than the horror of the unknown they had been living with.

“The North Vietnamese allowed the prisoners to begin communicating with their families,” Bette said. “It wasn’t much. He could only write six lines, and we could start sending him one ‘package’ a month – although we had no way of knowing if he received them – but at least we knew he was alive.

“Edward told us he was fine, but he was just trying to keep us from worrying.”

A couple of years later, though, Edward’s situation, in reality, became much better.

As a result of the agreed-upon terms of the Paris Peace Accords in January 1973, most U.S. troops were to be withdrawn from Vietnam, and all POWs were to be released from North Vietnamese prisons.

“The prisoners were released in the order in which they were shot down,” Bette said. “Edward was in the second group to be sent home. He was released on March 14, 1973.

Included in that number was the late U.S. Sen. John McCain.

“Words can’t describe how fantastic his return was,” Bette said. “The prisoners were first flown to Clark Air Force Base in The Philippines, then to Hawaii. He called me from Hawaii. That’s the first time I’d talked to him on the phone in five years.”

The Department of Defense arranged for Bette and the boys, and for Edward’s family in Purdy, to be flown to Oakland, Calif., to greet him upon his return.

Back on U.S. soil, Edward was under a doctor’s supervision for the next year, Bette said.

“He had physical injuries to overcome, including broken vertebrae and broken teeth, not to mention the emotional toll of five years spent as a prisoner,” she said.

Bette says there was also a type of culture shock Edward endured upon his return to California.

“A lot had happened in the United States in the five years that he’d been gone,” she said.

The war protests which, in part, had led to the de-escalation of the US presence in Vietnam were winding down, but many returning servicemen faced negative public sentiment upon their return.

By final tallies, over 500,000 U.S. troops had been committed in support of the South Vietnamese effort to keep communism at bay in their country. In that effort, 58,000 US servicemen lost their lives, as did almost 2 million troops and civilians in Vietnam and neighboring countries.

“The hippie movement was in full swing when Edward came home,” Bette said. “He was surprised to see me with long hair tied up in a French twist and wearing a miniskirt when I greeted him.

“For the boys, five years of him being gone was a lot, so they felt a little awkward around Edward at first.”

In southwest Missouri, residents in Purdy and Monett joined Edward’s parents and sister, as well as her husband, John Dodson, in rejoicing.

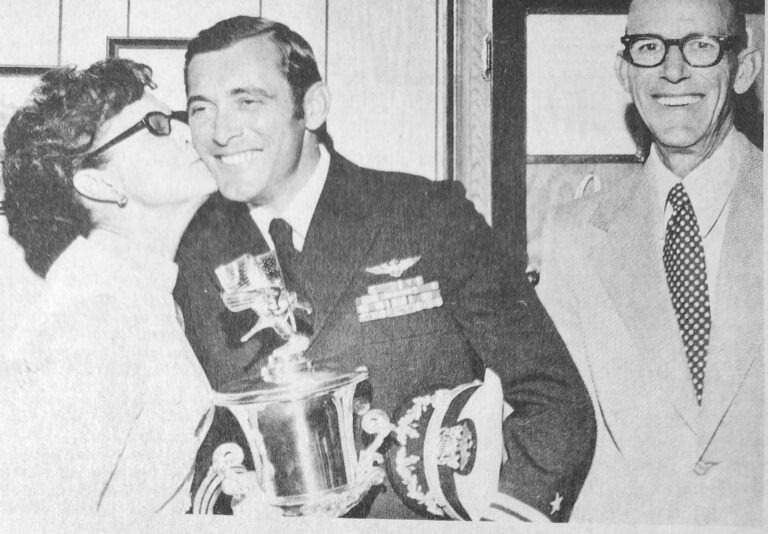

The American Legion Home in Monett hosted a huge homecoming celebration, where Edward thanked the large crowd in attendance for their support, which made it possible, he said, for the POWs to “come out with honor, and not on our knees.”

Another special ceremony for Edward to dedicate the A-4 Skyhawk mounted in the city park was held on July 23, 1977. The Skyhawk was donated to the City of Purdy by the U.S. Department of Navy as a result, in part, of the acquisition efforts of Edward’s good friend and high school basketball coach, Norman “Gabby” Gibbons, of Purdy.

In spite of the trauma Edward experienced as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam, he bounced back to continue his career with the Navy until his retirement in 1986.

Among his many military awards, a Silver Star Citation presented to Edward reads: “Through his resistance to brutalities [suffered as a POW from 1968-1973], [Edward Estes] contributed significantly toward the eventual abandonment of harsh treatment by the North Vietnamese, which was attracting international attention. By his determination, courage, resourcefulness, and devotion to duty, he reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the Naval Service and the United States Armed Forces.”

Edward’s faith in God and the support of his fellow POW’s got him through this life-changing experience, he later said.

“Edward always said he wouldn’t have changed anything in his life, because it made him the man he was,” Bette said.

At age 90, Cpt. Edward Estes “slipped the surly bonds of Earth” for his final flight on Oct. 7. He was buried with honors in Arlington National Cemetery.